Jefferson's Tombstone: Reflections on the Founding and the Founders of America on the Nation's 250th

News 30th January 2026 Stephen Blackwood

Here was buried

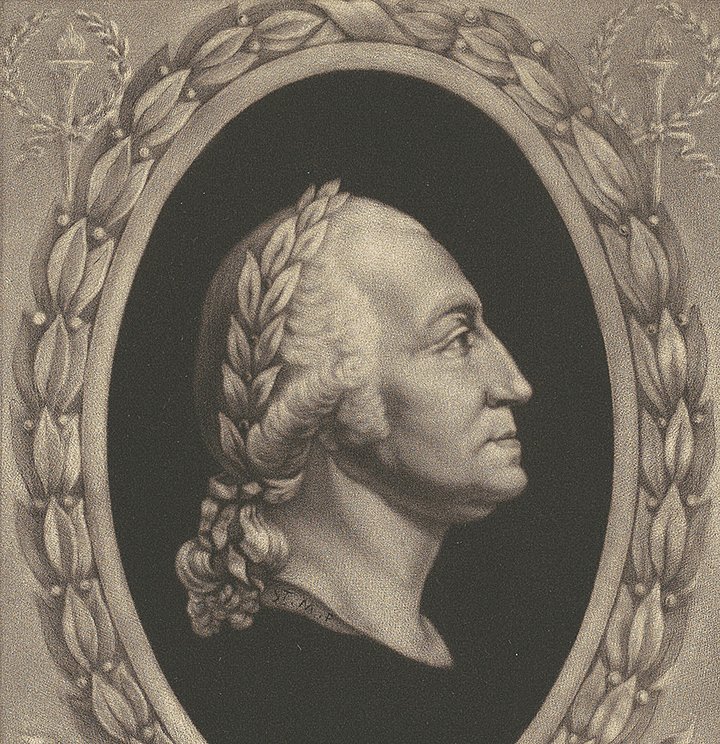

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

& Father of the University of Virginia

These words, engraved on a granite obelisk in the graveyard at Monticello, Virginia, are strikingly brief. It was, in fact, Jefferson’s express desire that his monument contain “not a word more”: it is “by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.” American liberty, religious freedom, and the founding of a new academic institution are the contributions worth recording. Not, it is extraordinary to say, his eight years spent as the third President of the United States of America.

Why did Jefferson think that founding a university should weigh more heavily than his central role in stewarding a new nation that was destined to reshape world history? To understand the principles that really mattered to this remarkable man, and to the Founding Fathers at large, we must step back a quarter-millennium to when the American dream was first forged.

Although amazed by the open-ended opportunities that their liberation from the shackles of King George III and the British Empire afforded, the Fathers did not seek to create their revolutionary country from nothing. On the contrary, they drew deep inspiration from history. But since most of the world had spent most of the last three millennia living under monarchs or autocrats, whether in small states or sprawling empires, it took particular focus to pick out those rare periods when republican rule, and even high-participation democracy, were miraculous historical outliers.

Tracing the threads of western civilization back to their source, like Theseus leaving the Labyrinth, led the Fathers to two points in place and time. First, to the Roman Republic, which sought to limit and balance any individual’s power, and largely succeeded for five centuries (509 BC – AD 27), after the overthrow of Rome’s initial monarchy (753–509 BC). Second, to the city states (poleis) of Classical Greece, which required active engagement from their (male) citizens – and sometimes to a remarkable degree, as in fifth- and fourth-century Athens. Yet, despite the importance of these two inspirational precedents, the Founding Fathers did not seek to emulate antiquity in every detail; its attendant social and cultural faults were not to be preserved for the sake of mere deference or role play. It was only the most noble ideals and the most successful structures that merited representation in the fledgling American republic.

This Classical knowledge helped make America. Yet despite the manifest reminders of classical architecture – and the pointed use of the Roman term Senate – the major role that Greece and Rome played in the formation of the United States is now largely obscured and forgotten. This year, as the United States marks its 250th anniversary since the Declaration of Independence, it is salutary to reflect once again on how Greek and Roman ideas – and ideals – inspired this bold venture of a kingless republic, and forged this most remarkable country.

As classically educated men, the Founding Fathers were steeped in the intellectual traditions of antiquity. Since their very youngest days the technicolor tales of Greece and Rome had animated their thoughts with heroes. Since there was no compulsion to the ancient world in any one particular form, they had the luxury to start from first principles and combine what seemed to them the best elements of Greek and Roman politics. The unstable nature of Athens’ direct democracy could be firmed up by locating it within the strict constitutional balances of Republican Rome. This project did not require archaeological autopsy or fanciful speculation: the surviving texts from titanic figures such as Aristotle, Polybius, Cicero and Livy, tempered by the critiques of Thucydides, Plato, Sallust, and Tacitus, offered almost direct access into the principles of ancient governance.

Why, the Fathers asked, did the Roman Republic fail and fall? It was because certain overbearing individuals – most notably Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar – found ways to circumnavigate the constraints of the system. They held power and wielded political influence that the Republic was never meant to sustain. The result of this override was the replacement of authoritative consuls, deliberating senators, and duty-bound citizens of Rome with five centuries of autocratic emperors. Such overbearing figures were frequently compared to America’s contemporary enemies, chief among them George III, Thomas Hutchinson, and in due course Aaron Burr. In contrast, the Fathers drew inspiration from those virtuous champions of liberty Cato the Younger, Cicero, and Brutus.

The Fathers found these heroes in the history books that fuelled their formative years. The biographical stories of Plutarch’s Lives – immensely popular, in Greek or English, throughout the eighteenth century – served up countless exemplars of moral rectitude, who were convenient blueprints for the Americans yet to be. Although George Washington differed from other Founding Fathers in not being deeply educated in the Classics, he had an intimate knowledge of the great figures sketched by Plutarch, including the Roman general Fabius Cunctator, whose principled decision to relinquish dictatorial power and return to his quiet rustic life was perfectly reflected in Washington’s leaving the presidential office to return to his Virginian farm.

John Adams, Washington’s successor as President, cultivated a life-long friendship with the Classics. As both a lawyer and statesman, Adams was drawn particularly to the figure of Cicero, not only a famously eloquent lawyer and statesman in Rome, but also a political philosopher in his own right. Cicero’s resistance to Julius Caesar’s unconstitutional dominion inspired these new American libertarians – just as it did his wife: Abigail Adams sometimes signed letters to John as “Portia”, acting as the wife of the Caesar-slaying Brutus. In his political philosophy, Adams was particularly influenced by the “mixed constitution” that Polybius set forth: this sought to combine elements from very different forms of government – not just democracy, but also aristocracy and even monarchy. A novel mix needed making.

As for Jefferson, he had studied Latin and Greek throughout his life, and spent formative years at William and Mary. He too held Cicero in the highest esteem: that man’s ideal of public service, honor in civic life, academic commitment to philosophy, and leisured, learned retirement were all important parts of how Jefferson conceived of Republican liberty. No less importantly, though, Jefferson was inspired by the ethics of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who he thought contained “everything rational in moral philosophy which Greece and Rome have left us”. Jefferson planned, in fact, to synthesize the teachings of the Christian Gospels with Epicurean moral philosophy. He admired Epicurus’ rich conception of personal happiness (eudaimonia), but stressed that it needed to be combined with active civic virtue, rather than the Epicurean ideal of complete retreat from political participation and the urban rat-race.

Such philosophical inspirations are manifest in the Declaration of Independence itself, where ancient ideas and Enlightenment principles join forces to set out the new America’s commitment to natural rights, individual dignity, and carefully calibrated self-governance. Since Jefferson was the primary author of the Declaration, the trained ear can hear how "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness" echoes his own summary of Epicureanism: “Happiness is the aim of life, virtue the foundation of happiness.”

The picture here is clear, and similarly deep classical study would go on to animate the next three presidents: James Madison, John Monroe, and – like father, like son – John Quincy Adams.

Let us now return to the question of why founding the University of Virginia mattered so much to Jefferson. It was patent to him, as to all the Founding Fathers, that their world of 1776 was ultimately a product of Greco-Roman ideas, inextricably intertwined with Christian doctrine. To understand the present and shape the future to come each American had to grasp the past. Yet although the classical world can provide deep insights about both self-government and the government of the self, it poses just as many questions as it answers. Understanding its complexity requires deep, careful, slow study and contemplation, ideally in the very languages of antiquity, Greek and Latin. The immense realm of antiquity, like any serious subject of study, needs to be approached by a harmonious community of scholars, engaged in shared enquiry but without any imposition of dogma, orthodoxy, or censorship. In Charlottesville Jefferson sought to create an “academical village” where freedom lay at its heart: “This institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” These were the very principles that animated the leaders of the United States of America.

How dreams can fade. The original tombstone of Jefferson, moved to the University of Missouri in 1884 when a replacement was commissioned for Monticello, has recently been encased in an inch-thick plastic protective case to save it from student vandalism—a plangent metaphor for the cancel culture and burn-it-all-down radicalism that dominate too many universities. Such institutions have become debased into the very opposite of what Jefferson intended: they are places that spread ideologies which corrupt and destroy, rather than propagate ideals which preserve and protect, our country and culture.

This cannot go on, not if our civilization is to have a future it can recognize. For Jefferson was right: only with the help of universities that transmit the principles and ideals on which our civilization depends can that it realize its future.

Ralston College, the institution of which I am proud to be president, was founded to do precisely this: to make a similar intervention in twenty-first-century society to that which Jefferson intended the University of Virginia to the fledgling United States of America. Ralston is fundamentally committed to four principles: the pursuit of truth, the defense of our freedoms – of thought, speech, inquiry, conscience, and association – the devotion to beauty, and the fostering of fellowship. Only by upholding these do we create the intellectual community that allows for the difficult but liberatory exploration of life’s most important and enduring questions. We give our students access to the ancient languages so that they too, like Jefferson and Madison before them, can directly engage with the very earliest authors of the western tradition as though they were speaking with friends. We don’t train our students how to lead in the world; we train them in and on the subjects that will allow them to be leaders in the world.

We now live in a hyper-partisan age, one riven by divisions more uncompromising than can be found in any Greco-Roman city state. Such factionalism never lives long before opening the door to authoritarianism, whatever the stripe. In Ancient Athens the Sophists found many stern critics because their combination of powerful rhetoric and self-serving motives led to the rise of the demagogue – the provocative figure who can rally the populace to ride roughshod over the deliberative process of democracy. Since our own era is beset by uprootedness, confusion, unrest and ignorance, we must find stability again. If America is still to stand for liberty, the truths of that freedom can only be guaranteed for the future by rekindling their flame – perennial, powerful, and a beacon to all who seek it – not tomorrow, but today.

SUPPORT A NEW BEGINNING

Education and conversation free from censorship, cynicism, and corruption matter. Ralston College is a place for them to happen, for human flourishing and building anew.